Future Methods, Callouts & Callbacks

Table of Contents:

Today we’re going to talk about “future” methods - Salesforce’s way of handling asynchronous code. For many, your introduction to future methods happens the first time that you need to integrate with an external API. Salesforce prevents you from performing any kind of synchronous API calls following DML operations; this is the “invisible hand” of SFDC guiding you to do things the way that they want you to — in other words, if you have begin your main thread operation with some kind of inserting / updating / upserting / deleting of SObject records, the code performing the API call needs to be pushed to another thread.

For many, future methods represent a distinct challenge when it comes to writing clean Apex code. They only accept primitive types, or collections; this means that most future methods end up taking in an Id or a List<Id> to then perform their work. That leads to tight coupling between the way API calls are being made, and the work that needs to be done once the call has finished. How can we batten down the hatches, write clean code, and still do work asynchronously?

Separating the Concerns in Async Apex Methods

At its heart, async work with API callouts can be broken down into three pieces:

- a future method must be static and can only accept object primitives: Strings, Integers, Ids, Lists, etc …

- a callout is performed

- some kind of follow-up work is done

Looking at the list like this, it’s almost like there are 3 classes waiting to be born. The truly tightly coupled concepts, written another way:

- a wrapper object representing the information necessary for the HTTP call

- a class that accepts that wrapper and holds itself responsible for HTTP calls

- the additional work that needs to be done can also be encapsulated … like a callback function in languages where functions are first-class citizens

This is the kind of test I’d like to write, showcasing the first two objects:

@IsTest

private class HttpCallout_Tests {

@IsTest

static void it_should_callout_successfully() {

Callout fakeCallout = new Callout('{parameter1: perhaps a serialized list or id!}',

new Url('https://api.com'), RestMethod.POST);

String jsonString = JSON.serialize(fakeCallout);

Test.startTest();

HttpCallout.process(jsonString);

Test.stopTest();

System.assertEquals(1, Limits.getCallouts());

}

}Setting up Callouts and HTTP Class Wrappers

The most basic implementations:

public class Callout {

private static final Integer DEFAULT_TIMEOUT = 10000;

public Callout(String jsonString,

Url endpoint,

RestMethod method,

Integer millisecondTimeout) {

this.BodyString = jsonString;

this.Endpoint = endpoint.toExternalForm();

this.RestMethod = method.name();

this.Timeout = millisecondTimeout;

}

public Callout(String jsonString, Url endpoint, RestMethod method) {

this(jsonString, endpoint, method, DEFAULT_TIMEOUT);

}

// sometimes an api key is supplied as part of the URL ...

// because it's not always necessary, we make it a public member of the class

public String ApiKey { get; set; }

public String BodyString { get; private set; }

public String Endpoint { get; private set; }

public String RestMethod { get; private set; }

public Integer Timeout { get; private set; }

}

public class HttpCallout {

@future(callout = true)

public static void process(String calloutString) {

Callout calloutObj = (Callout)JSON.deserialize(calloutString, Callout.class);

HttpRequest req = setupHttpRequest(calloutObj);

// this is the part you would try/catch

// in a more robuse implementation ...

new Http().send(req);

}

private static HttpRequest setupHttpRequest(Callout callout) {

HttpRequest req = new HttpRequest();

req.setEndpoint(callout.Endpoint);

req.setMethod(callout.RestMethod);

req.setTimeout(callout.Timeout);

req.setHeader('Content-Type', 'application/json');

req.setBody(callout.BodyString);

if(String.isNotBlank(callout.ApiKey)) {

req.setHeader('x-api-key', callout.ApiKey);

}

return req;

}

}So what do we achieve from this structure? We’ve successfully encapsulated the aspects surrounding an HTTP request. By itself, this isn’t necessarily very impressive; in fact, the test doesn’t even pass due to one of my favorite possible Apex exceptions:

System.TypeException: Methods defined as TestMethod do not support Web service callouts.

Sigh. Luckily you only need one boilerplate implementation of Salesforce’s included HttpCalloutMock interface in order to proceed. Unfortunately, it’s only within that HttpCalloutMock class that you can assert against Salesforce’s Limits.getCallouts() method to verify that a callout is indeed happening:

// slightly re-working HttpCallout ...

@future(callout = true)

public static void process(String calloutString) {

Callout calloutObj = (Callout)JSON.deserialize(calloutString, Callout.class);

HttpRequest req = setupHttpRequest(calloutObj);

makeRequest(req);

}

@TestVisible

private static HttpResponse makeRequest(HttpRequest req) {

return new Http().send(req);

}

// in HttpCallout_Tests ...

@IsTest

static void it_should_properly_stub_response() {

Test.setMock(HttpCalloutMock.class, new MockHttpResponse(200, 'Success', '{}'));

HttpResponse res = HttpCallout.makeRequest(new HttpRequest());

System.assertEquals(200, res.getStatusCode());

}

@IsTest

static void it_should_callout_successfully() {

Callout fakeCallout = new Callout('{parameter1: perhaps a serialized list or id!}',

new Url('https://api.com'), RestMethod.POST);

String jsonString = JSON.serialize(fakeCallout);

Test.setMock(HttpCalloutMock.class, new MockHttpResponse(200, 'Success', '{}'));

Test.startTest();

HttpCallout.process(jsonString);

Test.stopTest();

System.assert(true, 'should make it here!');

}

public class MockHttpResponse implements HttpCalloutMock {

private final Integer code;

private final String status;

private final String body;

public MockHttpResponse(Integer code, String status, String body) {

this.code = code;

this.status = status;

this.body = body;

}

public HTTPResponse respond(HTTPRequest req) {

System.assertEquals(1, Limits.getCallouts());

HttpResponse res = new HttpResponse();

if(this.body != null) {

res.setBody(this.body);

}

res.setStatusCode(this.code);

res.setStatus(this.status);

return res;

}

}Encapsulating the details behind an HTTP request inside of the Callout object isn’t, by itself, that impressive. You’re saving on lines of code in setting up your HttpRequest objects that would otherwise have to be performed each time you wanted to make a callout. You’re also reducing mental overhead by properly separating concerns; the HttpCallout object shown is very simple, but when you want to, say, add a try/catch block to your wrapper, you now know that there’s only one single place in the system where it’s necessary to try/catch for HttpRequests.

The real potential behind encapsulating your request information into the Callout object is what comes next — typically, the purpose of a callout is not only to send information to other systems. Sometimes that’s the case, and those cases are lucky — no further processing is required! But most of the time, you’re going to be getting information back from having made a callout in order to perform additional processing. This can typically lead to a lot of if/then statements, or perhaps a big switch statement following the HTTP section in your class.

In order to prevent our HttpCallout from growing in size beyond its concerns as the means of making HTTP requests, let’s borrow some terminology from languages where methods, or functions, themselves are first-class citizens. There is no System.Type for the methods within your classes themselves; no way to represent them for internal or external purposes. You can’t pass a function to your Callout object … but you can pass a class!

Introducing the Callback Object

When making use of future methods, it used to be that options were a lot more limited in terms of what kind of processesing could occur. Because operating in read/write mode was limited to async methods, and because one future method couldn’t call another future method, there wasn’t much you could do (beyond helper classes designed to setup HttpRequests) to safely encapsulate HTTP-related logic. Furthermore, future methods must return void, effectively limiting that separation of concerns even more.

Thankfully, a few years ago, Salesforce introduced the System.Queuable interface — a means of performing async work that could be called from within a future method. Defining a simple callback class becomes drop-dead simple, as a result:

public abstract class Callback implements System.Queueable {

private HttpResponse res;

public abstract void execute();

public void callback() {

System.enqueueJob(this);

}

public void callback(HttpResponse res) {

this.res = res;

this.callback();

}

}

// and the basic test:

@IsTest

private class Callback_Tests {

@IsTest

static void it_should_callback() {

CallbackMock mock = new CallbackMock(null);

// have to wrap in start/stop test again to force async execution

Test.startTest();

mock.callback();

Test.stopTest();

System.assertEquals(true, WasCalled);

}

static boolean WasCalled = false;

private virtual class CallbackMock extends Callback {

public override void execute(System.QueueableContext context) {

WasCalled = true;

}

}

}Right. We’re nearly there. Let’s define the Callback member on our Callout object:

public class Callout {

private static final Integer DEFAULT_TIMEOUT = 10000;

public Callout(String jsonString,

Url endpoint,

RestMethod method,

Integer millisecondTimeout,

Callback callback) {

this.BodyString = jsonString;

this.Callback = callback;

this.Endpoint = endpoint.toExternalForm();

this.RestMethod = method.name();

this.Timeout = millisecondTimeout;

}

public Callout(String jsonString, Url endpoint, RestMethod method, Callback callback) {

this(jsonString, endpoint, method, DEFAULT_TIMEOUT, callback);

}

// ...

public Callback Callback { get; private set; }

}And then in our wrapper object:

public class HttpCallout {

@future(callout = true)

public static void process(String calloutString) {

Callout calloutObj = (Callout)JSON.deserialize(calloutString, Callout.class);

HttpRequest req = setupHttpRequest(calloutObj);

HttpResponse res = makeRequest(req);

calloutObj.Callback.callback(res);

}

// ...

}To make things bullet-proof safe, we can even utilize the polymorphic empty object pattern for the Callback object once it’s been received by the Callout:

// in Callout.cls

public Callout(String jsonString,

Url endpoint,

RestMethod method,

Integer millisecondTimeout,

Callback callback) {

this.BodyString = jsonString;

this.Callback = callback != null ? callback : new EmptyCallback();

this.Endpoint = endpoint.toExternalForm();

this.RestMethod = method.name();

this.Timeout = millisecondTimeout;

}

public Callout (String jsonString, Url endpoint, RestMethod method) {

this(jsonString, endpoint, method, null);

}

// ...

private virtual class EmptyCallback extends Callback {

public override void execute(System.QueueableContext context) {}

}Let’s verify that a non-null callback can receive the HttpResponse and do something with it (the first test we wrote in HttpCallout_Tests covers the null callback case):

// in HttpCallout_Tests ...

@IsTest

static void it_should_callout_and_callback() {

HttpCallback mockCallback = new HttpCallback();

Callout fakeCallout = new Callout(

'{parameter1: perhaps a serialized list or id!}',

new Url('https://api.com'),

RestMethod.POST,

mockCallback

);

String jsonString = Json.serialize(fakeCallout);

Id fakeAccountId = TestingUtils.generateId(Account.SObjectType);

Test.setMock(HttpCalloutMock.class,

new MockHttpResponse(200, 'Success', '{ \""AccountId\"" : "'+ fakeAccountId +'" } ')

);

Test.startTest();

HttpCallout.process(jsonString);

Test.stopTest();

System.assertEquals(fakeAccountId, mockCallback.acc.Id);

}

// ...

private class HttpCallback extends Callback {

public Account acc { get; private set; }

public override void execute(System.QueueableContext context) {

MockApiResponse mockRes =

Json.deserialize(this.res.getBody(), MockApiResponse.class);

this.acc = new Account(Id = mockRes.AccountId);

// do other work and perform DML ...

}

}

private class MockApiResponse {

public Id AccountId { get; set; }

}Here I ran into my first snafu, as the test returns System.SerializationException: Not Serializable: System.HttpResponse. Circular references in JSON are fun! OK, let’s try something a little simpler:

public abstract class Callback implements System.Queueable {

protected string responseBody;

// ...

public void callback(HttpResponse res) {

this.responseBody = res.getBody();

this.callback();

}

}

// and in HttpCallout_Tests's HttpCallback object:

public override void execute(System.QueueableContext context) {

MockApiResponse mockRes = (MockApiResponse)

Json.deserialize(this.responseBody, MockApiResponse.class);

this.acc = new Account(Id = mockRes.AccountId);

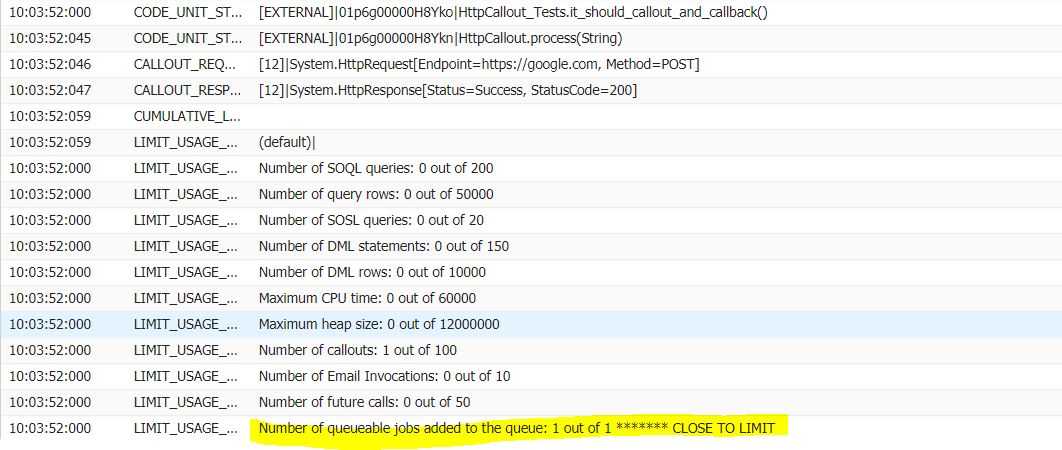

}This is where things started to get really weird. The test was still failing; the Account and its Id didn’t seem to be getting set. I backed off from what I was doing and asserted that there had been a Queueable job added to the queue. That failed. Peering at the log, though, things seemed to differ:

I did a little reading on the subject and didn’t come up with anything. I started debugging, and quickly ran into an issue that superceded what I had been looking into; namely, that the HttpCallback mock that I was initializing in my test wasn’t getting called at all when the test was being run. At this point, my writing was interrupted by a quick flight, and during my time in the air I finally realized the obvious (which may have already occurred to you) — namely that the serialization process for the Callback was losing the crucial pointer to the actual instance of the HttpCallback. When de-serialized, the only encoding that remained was for the dumbed-down abstract version of the Callback class. Bummer. There was no way to pass a specific instance for the Callback to the Callout object, after all. Or was there?

Undaunted, and with plenty of wifi-free time on my hands, I thought about my options. The entire point in writing this article was to explore how developers could move towards a more polymorphic approach to HTTP requests and their subsequent follow-up work. If the developer and team was confident that the Callout and HttpCallout objects were doing their part, testing could occur in isolation for concrete Callback implementations; reactions to different kinds of HTTP requests could be entirely decoupled from the fetching process. Not getting the callback idea to work would have been a big loss.

Callbacks, Redux

It was time to re-engineer the Callback object. It still needed to abstract out the Queueable Apex implementation, but it also needed to play nice with serialization, and couldn’t remain on the Callout object as a result. I went back to the drawing board:

public virtual class Callback implements System.Queueable {

private Type callbackType;

protected string responseBody;

protected Callback() {}

public Callback(Type callbackType) {

this.callbackType = callbackType;

}

public void callback() {

System.enqueueJob(this);

}

public void callback(HttpResponse res) {

this.responseBody = res.getBody();

this.callback();

}

public virtual void execute(System.QueueableContext context) {

if(this.callbackType == null) {

this.callbackType = EmptyCallback.class;

}

((Callback) this.callbackType.newInstance())

.load(responseBody)

.execute(context);

}

protected Callback load(String responseBody) {

this.responseBody = responseBody;

return this;

}

private class EmptyCallback extends Callback {

public override void execute(System.QueueableContext context) {

// do something like debug here

// or just do nothing, like the name suggests!

}

}

}

// and in the test ...

@IsTest

private class Callback_Tests {

@IsTest

static void it_should_callback() {

Callback mock = new Callback(CallbackMock.class);

Test.startTest();

mock.callback();

Test.stopTest();

System.assertEquals(true, MockWasCalled);

}

static boolean MockWasCalled = false;

public virtual class CallbackMock extends Callback {

public override void execute(System.QueueableContext context) {

MockWasCalled = true;

}

}

}Now the empty callback itself is encapsulated within the Callback object — which actually works much more nicely than the Callout being concerned with whether or not to add an empty callback. The addition of the load method is how we’ll pass the results of the HttpRequests into callbacks which are concerned with responding to them; this is to get around the fact that the newInstance() Type method accepts no other arguments. While I haven’t shown the code for it here, the astute reader might also note that zero-argument constructors play very nicely with the Factory Pattern, due to the fact that the Factory can be initialized within any object’s constructor and still be over-ridden in tests.

I’ll also just explicitly mention that the callback() method without arguments is meant for further re-use within your codebase. The Queuable interface is ideal for use cases where you don’t want to perform Batch Apex (which, while powerful, is slow — and requires way more boilerplate) but do need to push things async due to performing DML, and you’d like easy access to recursion. The CallbackMock just shown gives you an idea of how little code you need to write in order to start moving — all you need to do if you’re not concerned with HTTP is extend the Callback class and override the execute method. If you need recursion, you can just call callback() at the end of your execute method to get things re-queued up.

Of course, our HTTP consumers still need some code tweaks:

// in Callout.cls

public Callout(

String jsonString,

Url endpoint, RestMethod method,

Integer millisecondTimeout,

Type callbackType) {

this.BodyString = jsonString;

// Type.forName throws for nulls, alas

this.CallbackName = callbackType == null ? '' : callbackType.getName();

this.Endpoint = endpoint.toExternalForm();

this.RestMethod = method.name();

this.Timeout = millisecondTimeout;

}

public Callout(String jsonString, Url endpoint, RestMethod method, Type callbackType) {

this(jsonString, endpoint, method, DEFAULT_TIMEOUT, callbackType);

}

public Callout (String jsonString, Url endpoint, RestMethod method) {

this(jsonString, endpoint, method, null);

}

// ... and the member within Callout is also defined:

public String CallbackName { get; private set; }Which makes the HttpCallout class look like …

public class HttpCallout {

@future(callout = true)

public static void process(String calloutString) {

Callout calloutObj = (Callout)JSON.deserialize(calloutString, Callout.class);

HttpRequest req = setupHttpRequest(calloutObj);

HttpResponse res = makeRequest(req);

Type callbackType = Type.forName(calloutObj.CallbackName);

new Callback(callbackType).callback(res);

}

// ...

}

// and in HttpCallout_Tests:

@IsTest

static void it_should_callout_and_callback() {

Type callbackType = HttpCallbackMock.class;

Callout fakeCallout = new Callout(

'{parameter1: perhaps a serialized list or id!}',

new Url('https://api.com'),

RestMethod.POST,

callbackType);

String jsonString = Json.serialize(fakeCallout);

Id accountId = TestingUtils.generateId(Account.SObjectType);

Test.setMock(

HttpCalloutMock.class,

new MockHttpResponse(200, 'Success', '{ "AccountId" : "' + accountId + '"}')

);

Test.startTest();

HttpCallout.process(jsonString);

Test.stopTest();

System.assertEquals(accountId, mockId);

}

private static Id mockId;

private class HttpCallbackMock extends Callback {

public override void execute(System.QueueableContext context) {

FakeApiResponse fakeResponse =

(FakeApiResponse)Json.deserialize(this.responseBody, FakeApiResponse.class);

mockId = fakeResponse.AccountId;

// do other work and perform DML ...

}

}

private class FakeApiResponse {

Id AccountId { get; set; }

}If you’ve made it this far, none of this should come as a surprise. One thing that did come as a surprise to me — though it makes sense thinking about it now — is that the test classes extending Callback had to be public in order for them to be properly constructed by the newInstance Type method.

Closing Thoughts On Future Methods, Callouts & Callbacks

I have been wanting to incorporate this design into some of my orgs for a while, and while there were some hiccups along the way, I consider them valuable learning experiences.

The ability to decouple our HTTP-related code from how consumers needing to make API calls choose to respond to requests is extremely valuable; it lets us test our production-level code without having to keep re-testing the underlying basics (making the request, try/catching the response, etc …). And while a future method can’t call a future method, Queueable Apex can nearly endlessly be chained together (so long as your maximum enqueued jobs don’t exceed 50, the Salesforce limit for Queueable Apex). This means your Callback objects can be encapsulating further callbacks in turn within their own execute methods … a powerful combo, particularly if you need to interact with more than one API at a given time (you’ll need to also implement Database.AllowsCallouts on the Callback object if you need to perform further API calls).

There are of course many different ways to implement future and Queueable methods within Apex; everybody has a different use case, as they say. Still, it’s my hope that this article has gotten you thinking about how you might best create reusably async Apex within your own codebase(s). I’ve uploaded the example code shown here in various iterations on the Apex Mocks repo, in the hopes that it will prove useful. If you enjoyed the Callback pattern, I would highly recommend checking out my article on Round Robin Assignment, as well as the article on open sourcing the Round Robin Assigner, as they make usage of a similar pattern — the Visitor pattern — which makes for some good, related reading.

Thanks for staying with me and stay tuned for more on The Joys Of Apex!